Introduction | Heinz Kohut | The Self | The Selfobject

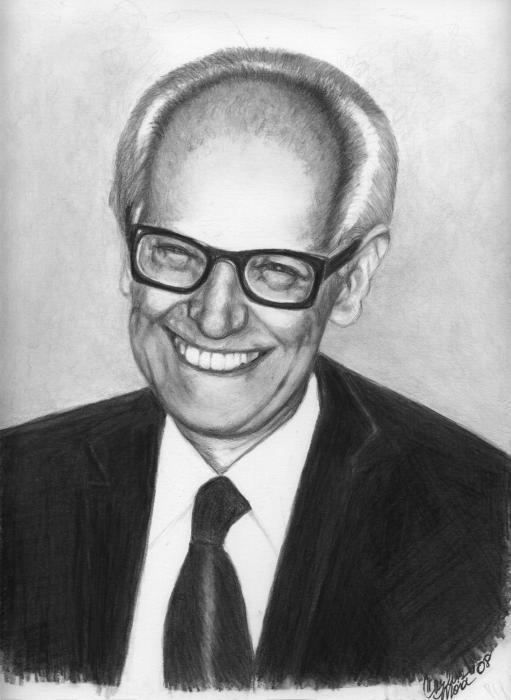

Welcome to the Self Psychology Psychoanalysis website, sponsored by The New York Institute for Psychoanalytic Self Psychology. It is committed to the study and advancement of the work of Heinz Kohut, the founder of self psychology, whose work has opened the door to endless discoveries of the mental life of patients.

Kohut's concepts were born out of psychoanalytic treatment, and he was clear that the central focus of self psychology was its attention to the development and analysis of the transferences:

"Self psychology does not advocate a change in the essence of analytic technique. The transferences are allowed to unfold and their analysis - the understanding of the transference reactions, their explanation in dynamic and genetic terms - occupies, now as before, the center of the analyst's attention"("How Does Analysis Cure", 1984, p. 208).

This web site acts as a forum for those who are interested in the study of Kohut's work. Papers will be presented by guest authors in the Papers section. Relevant questions and comments will be welcomed and published.

A theory introduced by Heinz Kohut in the early 70's with the publication of his now famous monograph, The Analysis of the Self (1971), self psychology has burgeoned into the most significant analytic theory since Freud first introduced psychoanalysis to the scientific world in the early 20th century.

Having been trained in the theories of American ego psychology, Kohut established a reputation as a staunchly conservative Freudian analyst, winning him in 1964 the presidency of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Yet it was his integrity, not his politics, and his deep concern for the many stalemated or premature terminations among his patient population, that eventually prompted him to question the very theories upon which he had staked his scientific surety and built his reputation.

When asked by a fellow scientist what had caused him to alter his thinking, he readily admitted that he "had more and more the feeling that my explanations [to patients] became forced and that my patients's complaints that I did not understand them…were justified" (Kohut, 1974, pp.888-889).

Setting aside his classical theory, Kohut took the lead from his patients in discovering his theory of the self. In particular, it was the case of Ms. F., a woman in her mid-20's, who insisted that he be perfectly attuned to her every word.

This taught Kohut (1968, 1971) about empathy as experience-near observation, the clinical stance from which he would make his major discoveries.

For example, whenever Kohut strayed from Ms. F.'s experience by offering an intervention that reflected even a slight revision to what she had arrived at on her own, she became enraged that he was ruining what she had accomplished and "wrecking" her analysis.

By relinquishing his clinical assumption that her anger was an expression of her resistance to the analysis, which he recognized was impeding his ability to grasp the fullness of Ms. F.'s experience, Kohut learned to see and understand things exclusively from her viewpoint.

He termed this mode of observation, experience-near.

Thus, in these moments when he captured her feeling of being misunderstood and offered a response that more or less reflected what she was thinking and feeling, he observed that her previous sense of well-being was quickly restored.

In time Kohut hypothesized that this sequence of disruption and reparation of the empathic connectedness between analyst and analysand is an inevitability in any effective treatment; at the same time, he suggested that if these disruptions of empathy are kept to an "optimal" (vs. "traumatic") level, they are not harmful but, in fact, are an essential ingredient in the development of psychic structure and analytic cure.

These initial observations from an experience-near empathic perspective led to Kohut's understanding of Ms. F.'s need for recognition, a need he viewed as a "developmental arrest" due to empathic failures of childhood and that he later theorized to be a mirror selfobject transference.

Thus, it is this experience-near mode of observation that Kohut viewed as empathy.

Perhaps no one since Freud has jogged the collective sensibility of the psychoanalytic community more than Heinz Kohut. Since his celebrated works were introduced, there has been an outpouring of scholarly literature explaining and elaborating on his theories of self psychology, applying them to the existing body of knowledge in the mental health field. Kohut's theory of the self is both the culmination of his lifelong work and the fullest expression of his unique creativity, empathy, and courage.

Every scientific theory is the natural outgrowth and extension of its creator, and self psychology is no exception. Although Kohut emphasised that the personality of the author of a scientific work should not influence one's evaluation of the work itself, we think that some appreciation of Kohut's life and how he arrived at his theori theories will enhance the reader's understanding.

Heinz Kohut was born on 3 May 1913 in Vienna, and died 8 October 1981 in Chicago, where he had lived for over forty years. There has been relatively little written about his life, except for a brief biographical sketch, written by Charles Strozier(1). Other information about him can be gleaned from a thumbnail sketch of Kohut's work in Time Magazine(2), and the obituaries written by Montgomery(3) and Goldberg(4).

As an only child, his precocious abilities were recognized at an early age. He was born in Vienna and spent his childhood and early adulthood there. He attended the local elementary school and later the Doblinger Gymnasium where he excelled academically, and regularly participated in sports such as track and boxing. His many references to such well-known figures as Beethoven, Thomas Mann, Dostoyevsky, Horace and the like derived from his thorough grounding in a classical education that included Latin, Greek, French, science, and world literature. Kohut was tutored between the ages of 8 and 14 by a young university student. This young man played an important role in his intellectual and emotional development. Goldberg recounts a "complex and erudite" game that Kohut and his tutor would play, a version of "Guess What I'm Thinking" and "Twenty Questions." The objective of the game was to imagine what would have occurred in world history if a particular event had not taken place or a particular historical figure had not lived. For example, how would the world be different if Hannibal had not crossed the Alps or Caesar had not been assassinated? This rigourous mental game not only expanded his knowledge of history - something Kohut was noted for - but also developed observation skills similar to those that would serve him so effectively as a psychoanalyst. Such skills would evolve from the need to imagine, during this childhood exercise, what it would be like for an individual to live in a certain society or culture.

He went on to study medicine at the University of Vienna and received his medical degree there. During this time he became interested in psychoanalytic ideas and underwent an analysis with August Aichorn. In all his years in Vienna, Kohut never spoke with Freud. However, he frequently recounted having seen his "admired master" at the railroad station when Freud left Vienna to escape the Nazis in 1938. For Strozier the fondness with which Kohut told of this experience suggested "…continuities and Viennese connections…[…[and] a special sense of mission that he felt about psychoanalysis as a young man" (p. 6).

Kohut departed from Vienna a few months later. He settled in England for a time and then emigrated to America in 1940. He took his specialty training in neurology at the University of Chicago and was widely recognized as one who would have an impact on his field. However, he soon shifted interests and professional pursuits from neurology to psychoanalysis. He received his analytic training at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis, and upon graduation was appointed faculty member and training analyst. This was indeed an honour for one so relatively inexperienced. He was trained in the classical tradition of psychoanalysis, modified by the clinical and theoretical advances of the American ego psychology school of Hartmann, Kris, and Lowenstein. This tradition was grounded in the two basic Freudian principles of

Kohut became an advocate of these theories in his teaching, lecturing, and writing, and soon developed the reputation of being a conservative Freudian theorist. His views brought him the public admiration of such psychoanalytic luminaries as Anna Freud, Kurt Eissler, and Heinz Hartmann. In 1964 he was elected President of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Following this he was elected Vice President of the International Psychoanalytic Association and retained the position for nine years. This period earned him among his colleagues the affectionate title of "Mr. Psychoanalysis." It was, therefore, surprising when Kohut shifted his clinical views. Many of his colleagues, who had given him so much recognition just a short time before, now rejected him. His writing of the mid to late sixties questioned many of the psychoanalytic principles he had previously defended. But what had occurred to turn him around? What made him question the previously unquestioned? What made him reconsider the very theories of psychoanalysis that had so long guided his thinking and his clinical practice?

Kohut's clinical and theoretical perspective was considerably broadened by the case of Miss F. (Kohut 1968, 1971), which opened his eyes to significantly different psychic perceptions. Briefly, Miss F., a 25-year-old woman, had insisted that Kohut be nearly perfectly attuned to what she was saying. If, for example, he made any intervention that went beyond what she had said or learned in the therapy, she would become enraged. Kohut was initially firm in his theoretical belief that her protests were defensive and hid the underlying issues. Miss F. persisted in her complaints that he was "not listening," that he was "undermining her," that his remarks "had destroyed everything she had built up," and that he was "wrecking her analysis." Kohut realised that she would become calm only when he summarized or repeated what she had already said. Miss F.'s persistence in her complaints, together with Kohut's awareness of what calmed her, helped him to suspend his theoretical assumption that she was being defensive and to understand the importance of her need for confirming and mirroring responses. Furthermore, he realized that his interventions had not only not been helpful but, in fact, were adding to her problems. Through his work with Miss F., Kohut began to formulate his ideas about the developmental need for mirroring, as well as the mirroring selfobject transference.

It was treatment experiences such as these that prompted Kohut, in a letter dated May 16, 1974 (The Search for the Self, vol. 2), to respond so frankly to a fellow scientist, openly admitting that the one factor which had caused him to reconsider his theoretical perspective was the fact that he felt "stumped" by a large percentage of his cases in which treatment either stalemated or was prematurely terminated. In the letter he wrote: If I tried to explain their relationship to me, their demands on me, as revivals of their old love and hate for their parents, or for their brothers and sisters, I had more and more the feeling that my explanations became forced and that my patients' complaints that I did not understand them…were justified. [pp. 888-889]

His prolonged empathic immersion in the inner world of these same patients opened him to new and previously unrecognized psychic configurations. He continued:

It was on the basis of feeling stumped that I began to entertain the thought that these people were not concerned with me as a separate person but that they were concerned with themselves; that they did not love me or hate me, but that they needed me as part of themselves, needed me as a set of functions which they had not acquired in early life; that what appeared to be their love and hate was in reality their need that I fulfill certain psychological functions for them and anger at me when I did not do so. [pp. 888-889]

He outlined his thoughts on narcissism in his paper, "Forms and Transformations on Narcissism," which was published in the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association in 1966 (5). This paper formed the nucleus of his first book, The Analysis of the Self, published in 1971 (6).

As his ideas began to spread in the late sixties, rejection of him by his friends and colleagues intensified. Naturally these rejections hurt Kohut deeply, but they did not deter him from continuing his work. Many wanted to brand him as a dissident and to accuse him of founding a new school. However, he remained steadfast in his belief that his theory of the self was a further development and extension of psychoanalysis.

Though he lost a number of his valued friends and supporters, not all of them turned away. Many younger colleagues, who were former students of his and candidates at the Chicago Institute, gathered around him to form a study group similar to Freud's Wednesday Evening Society. They met regularly to discuss his evolving ideas. The initial membership of the group consisted of John Gedo, Arnold Goldberg(11), Michael Franz Basch (7), Paul Tolpin, Marian Tolpin, Paul Ornstein (8), Anna Ornstein, and Ernest Wolf (9). Over the years many others joined. A valuable purpose of the group was to offer Kohut a buffer against the potentially distracting public attacks of critics and to support him in the completion of his work. The group brought with them an enthusiasm for his ideas that buoyed Kohut and eventually culminated in his 1971 monograph, The Analysis of the Self, followed by his 1977 book,The Restoration of the Self(10).

While many of the psychoanalytic community viewed his theory of the self as heretical, there were many who respected his ideas and applied them in their work. Evidence of the growing impact that his theories were having was seen in the high attendance at the annual conferences on self psychology that were held around the country. For example, in 1980, 1,100 mental health professionals attended the Boston conference.

As a result of fading health, Kohut felt an urgency to complete his work and was forced to conserve his energy by limiting his speaking engagements. In those instances when he chose not to accept an invitation, he on, he frequently sent his trusted colleagues to discuss his ideas and to answer his critics. Unfortunately, this was seen as being "isolationist." It was also interpreted by others as an expression of Kohut's avoidance of facing his critics.

Kohut's final speech, "Reflections on Empathy," was given at the 1981 self psychology conference in Berkeley, California. He was aware he was dying, and at the conclusion of his speech he announced his final farewell. The audience, moved by his words, stood to express its deep appreciation. When the applause went on and on, Kohut gently raised his hands, interrupting the ovation, and quietly said, "I know your feelings...I want to rest now." He died four days later on Thursday, October 8, 1981.

How Does Analysis Cure?(12) was his final book, published posthumously in 1984. This work offered new perspectives on the place of empathy in analytic cure, and it expanded the concepts of defense and resistance; moreover, perhaps most importantly, it offered directions that we can pursue to understand more fully the human condition.

Through his experience-near empathic mode of observation during psychoanalysis, Kohut traced the development of the self not as a concept or representation of the mind as in object relations theory but as a "supraordinate" construct that comprises the entire psychic structure, that is, an inner experience that has continuity in time and space.

The particular patients he observed, such as the previously described Ms. F., were termed narcissistic personality disorders - later referring to them as self disorders - who presented with a clearly defined syndrome.

Characterized by unusually labile moods and extreme sensitivity to failures, disappointments, and slights, these patients are ultimately diagnosed not so much b much by the symptoms as by the emergence in treatment of certain unresolved needs he termed selfobject transferences.

By selfobject Kohut (1971, 1984) means the experience of another – more precisely, the experience of impersonal functions provided by another – as part of the self.

A final definition of selfobject was formulated by Ernest S. Wolf (9) (1988, p. 184): "Precisely defined, a selfobject is neither self or object, but the subjective aspect of a self sustaining function performed by a relationship of self to objects who by their presence or activity evoke and maintain the self and the experience of selfhood."

Selfobject transference, therefore, is the patient's experience of the analyst as an extension or continuation of the self, that is, as fulfilling certain vital functions that had been insufficiently available in childhood to be adequately transformed into reliable self structure.

He came to discover that within the empathic treatment milieu unmet infantile needs for recognition, idealization, and twinship reemerge in the form of mirroring, idealizing, and twinship selfobject transferences.

The growth-producing process by which these patients are able to internalize the needed selfobject functions and to acquire the missing self structure is termed transmuting internalization.

Kohut (1984, p. 70) came to recognize that this process occurs through this two-step process.

It is the empathic process of understanding and explaining - paralleling the therapeutic process of traditional analysis - that allows the treatment to go forward and the self to acquire the missing structures in what Kohut (1984) describes as a three-step movement.

Basch, M.F. (1983). Empathic understanding: A review of the concept and some theoretical considerations. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 31, 102-126.

Goldberg, A. (1980). Compassion, empathy, and understanding. In J. Mishne (Ed.), Psychotherapy and Training in Social Work (pp. 230-240). New York: Gardner Press.

Kohut, H. (1959). Introspection, empathy, and psychoanalysis: An examination of the relationship between mode of observation and theory. In P.H. Ornstein (Ed.), The Search for the Self (Vol. 1, pp. 205-232). New York: International Universities Press.

———1968. The psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders: outline of a systematic approach. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 23, 86-113.

———1971. The Analysis of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

———1974. Letter of May 16, 1974. In P.H. Ornstein (Ed.), The Search for the Self (Vol. 2, pp.888-891). New York: International Universities Press.

———1975. The psychoanalyst in the community of scholars. In P.H. Ornstein (Ed.), The Search for the Self (Vol. 2, pp.685-724). New York: International Universities Press.

———1977. The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

———1981. On empathy. In P.H. Ornstein (Ed.), The Search for the Self (Vol. 4, pp.525-535). New York: International Universities Press.

———1984. How Does Analysis Cure? Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

———1987. The Kohut Seminars on Self Psychology and Psychotherapy with Adolescents and Young Adults. New York: Norton.

Rowe, C. and MacIsaac, D. (1989). Empathic Attunement: The "Technique" of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology. Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

Strozier, Charles B. (2001). The Making of A Psychoanalyst. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Wolf, E.S. (1988). Treating the Self: Elements of Clinical Self Psychology.. New York: Guilford Press.

return to Home page